|

| Fig. 1 |

In 2019 we trapped the first apple maggot fly on around the end of June at about 1150 Degree Days from January 1. We are at 1016 DD as of today at 5:53 PM, so it is time to get out the apple maggot traps and get them set. I set our orchard's traps a few days ago and , as of yet, have no flies trapped. It only takes one non-baited trapped fly to determine that they have arrived to the orchard! The apple maggot (AM) is native to the Midwestern US and is considered a primary pest, along with plum curculio (PC), and codling moth (CM), which have been covered in previous posts. The adult apple maggot fly resembles a small housefly in size, with a black body, eyes of dark red, with the thorax and abdomen having distinctive white or cream colored bands. The AM is distinguished from other similar, and closely related flies, like cherry fruit fly and black cherry fruit fly, by the variation in dark banding on its wings (See Fig. 1).

|

| Fig. 2 |

The AM overwinters in the pupal stage in soil. As soil temperatures rise in early spring, development of pupae commences. The adult fly first emergence begins shortly thereafter (early summer, mid to late June in upper Illinois). It takes about 7 to 10 days for the female to mature enough to mate and lay eggs. So there is a 7 - 10 day window for spraying prior to egg laying. A feeding and mating period (pre-oviposition) during this 7-10 days is followed by egg laying directly under the skin of the apple. Females may deposit eggs over an approximate 30 day period laying as many as 300-500 eggs.

|

| Fig. 3 |

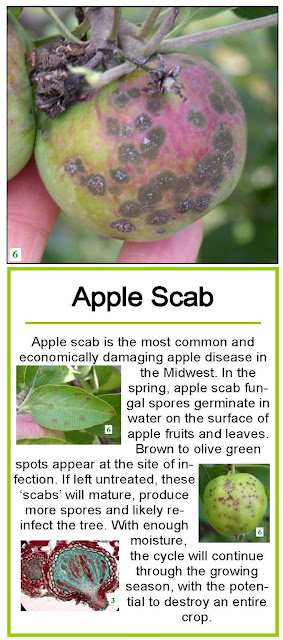

Egg-laying punctures cause dimples and distortion in the outer flesh of fruits. These punctures appear as pinpricks on the fruit surface. Larvae tunnel throughout the fruit leaving irregular trails.(Fig. 2) As eggs hatch, larvae funnel through fruit flesh leaving a winding brown trail.(Fig. 3) Egg laying usually ceases in early to late August; however, it may continue longer if drought conditions exist throughout August.

Monitoring For Apple Maggot

|

| Fig. 4 |

Hang the sphere in the proximity to fruit at eye level on the perimeter of the south or southeast side of the tree. Attach the ball in a sturdy stem about 1 foot above a fruit cluster of approximately 6-10, cleaning out the foliage and other fruit for at least 18 inches to sides and top of the trap so it is easily visible. The spheres attract the insects that come within a few yards of them; therefore, the capture of ONE AM on any one non-baited trap at a time would indicate the need for an immediate control application. The capture of 5 flies on a baited trap would indicate the need for an immediate control application. Once the pesticide is applied, AM captures are disregarded for the period during which the protective spray is effective (varies according to pesticide used).

Control for Apple Maggot

|

| Fig 5. |

Several insecticides can be used for apple maggot control including those used for codling moth control like and/or spinosad. Acetamiprid is a soft, conventional control and is available as Ortho Flower, Fruit & Vegetable Insect Killer (Fig. 5). This is a ready to use product that contains .006% acetamiprid, a synthetic organic compound of the family of chemicals that acts as neonicotinoid insecticides. Acetamiprid is a contact insecticide for sucking-type insects and can be applied as a foliar spray or a soil treatment. Acetamiprid acts on a broad spectrum of insects, including aphids, thrips, plum curculio, apple maggot and Lepidoptera, especially codling moth. When sprayed in the evening at sunset, it will not harm bees or other beneficial insects. Be sure to follow all label directions on the bottle for proper application.

|

| Fig. 6 |

As always, be sure to follow all label directions on the bottle for proper application.

For additional information, see the following fact sheets and guides which are available from local university extension services:

______________________________________________

Reference in this blog to any specific commercial product, process, or service, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement, recommendation, or certification of any kind by Royal Oak Farm, Inc. People using such products assume responsibility for their use in accordance with current label directions of the manufacturer.

Reference in this blog to any specific commercial product, process, or service, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement, recommendation, or certification of any kind by Royal Oak Farm, Inc. People using such products assume responsibility for their use in accordance with current label directions of the manufacturer.