Apple scab is the most prevalent and most damaging disease to apples we have in the Midwest. We are now officially emerging into the apple scab season and scab sprays should be applied according to the spray guide protocol. In the spring, once temperatures rise above the 42 degree or so mark, apple scab fungal spores can germinate in water on the surface of apple tree leaves and eventually, on the fruit itself. The water or moisture that is on the leaves is termed "leaf wetness". The spores will germinate once the leaves are wet for a certain period of time at temperatures above 42 degrees On the leaves, olive green to brown spots appear on the site of the infection. If the leaves have not been protected from this "primary" scab infection, the spores will mature and produce more spores during "leaf wetness" periods and move onto the apples where they form a "scab" like lesion, if the fruit is not protected. We call the lesions on the apples "secondary" scab. With enough moisture (leaf wetness), the cycle continues throughout the growing season and destroys the crop. Each leaf wetness event at the proper temperature that occurs during the early growing season is called and infection period.

Managing Apple Scab

The apple scab fungus survives in dead leaves on the ground and over winters there on the leaves. A lack of spring rains can reduce its importance, but as a rule, apple scab

requires yearly spray treatments. And, ornamental

crab apples are also hosts. As plant parts mature and the weather gets

warmer, susceptibility to this disease decreases, usually in late June, but pinpoint scab can

occur during extended periods of moisture during summer. The main objective in scab management is the reduction or prevention of

primary infections in spring. Extensive primary infections result in

poor fruit set and make scab control during the season more difficult.

If primary infections are successfully controlled, secondary infections

will not be serious. The key to success in scab control is exact timing

and full spray coverage. Wet periods, temperature, and relative humidity are

important factors. Because scab control often is part of a combination

treatment aimed at other diseases and insect control, choice of

materials and timing are also extremely important.

How Can an Infection Period be Determined?

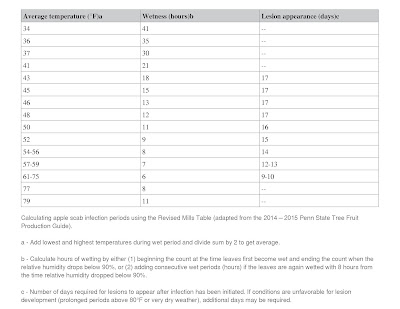

Apple scab infection periods can be predicted based on temperature and moisture (leaf wetness)

conditions. The Mills Table below, derived from research by Mills and La

Plante, gives hours needed at various temperatures under constantly wet

conditions for primary spores (ascospores) to cause infection in spring.

This system for forecasting scab and timing sprays has been validated

for apple-growing regions in the Midwest.

To Spray or Not To Spray

Monitoring for apple scab can be quite complicated for the home grower. But there is an alternative. Unless wetness periods are being monitored as outlined in the section

above, you can simply apply protective or eradicant fungicides at regular intervals beginning with green tip. Spraying should be done every 7 to 10 days, depending on the number of rain events between sprays. If there are no rain events between sprays, a single protectant spray will last at least 10 days but not more than 14 days, based on the product's label directions. You will need to make sure that your trees and fruit are protected prior to any rain event if you are going to use only a protectant. A good protectant is Captan or Mancozeb. But, a protectant can lose its effectivness after 2" of rain, so you also want to keep and eradicant on hand like a myclobutanil, which is available as Spectracide Immunox. A protectant like Captan has to be applied prior to a rain event. If no protection is available during the wetting event, then only an eradicant like Immunox can be applied that has a reach back of at least 48 hours. That means that it can still have an effect on the scab pathogen for up to 48 hours after a wetting event. A good option is to actually use both a protectant and an erdicant at the same time, like Captan mixed with Immunox, which will give you both protection and eradicant action after a wetting event. Be sure to monitor wetness periods throughout the spring to insure that trees are always adequately protected.

Monitoring for apple scab can be quite complicated for the home grower. But there is an alternative. Unless wetness periods are being monitored as outlined in the section

above, you can simply apply protective or eradicant fungicides at regular intervals beginning with green tip. Spraying should be done every 7 to 10 days, depending on the number of rain events between sprays. If there are no rain events between sprays, a single protectant spray will last at least 10 days but not more than 14 days, based on the product's label directions. You will need to make sure that your trees and fruit are protected prior to any rain event if you are going to use only a protectant. A good protectant is Captan or Mancozeb. But, a protectant can lose its effectivness after 2" of rain, so you also want to keep and eradicant on hand like a myclobutanil, which is available as Spectracide Immunox. A protectant like Captan has to be applied prior to a rain event. If no protection is available during the wetting event, then only an eradicant like Immunox can be applied that has a reach back of at least 48 hours. That means that it can still have an effect on the scab pathogen for up to 48 hours after a wetting event. A good option is to actually use both a protectant and an erdicant at the same time, like Captan mixed with Immunox, which will give you both protection and eradicant action after a wetting event. Be sure to monitor wetness periods throughout the spring to insure that trees are always adequately protected. More About Fungicides

Fungicides can be contact fungicides or penetrant fungicides and non-systemic, locally systemic or systemic. Mobility describes fungicide movement after it is applied to a plant. To understand differences in mobility, it’s important to know the difference between absorption and adsorption.

Fungicides that can be taken up by the plant are absorbed. Fungicides that adhere in an extremely thin layer to plant surfaces are adsorbed. Because fungicides are either adsorbed or absorbed, they have two basic forms of mobility: contact and penetrant. Regardless of the type of mobility that a fungicide possesses, no fungicide is effective after the development of visible disease symptoms. For that reason, timely fungicide application before establishment of the disease is important for optimal disease management.

Contact fungicides are adsorbed and considered non-systemic. They are susceptible to being washed away by rain or irrigation, and most (but not all) do not protect parts that grow and develop after the product is applied. Captan is one such contact fungicide.

Penetrant fungicides are absorbed, so they move into plant tissues, and penetrate beyond the cuticle and into the treated leaf tissue itself. There are various kinds of penetrants, characterized by their ability to spread when absorbed by the plant. They can be locally systemic, penetrating leaf tissue only or systemic, moving beyond the leaf tissue. Systemic fungicides can be further subdivided based on the direction and degree of movement once they have been absorbed and translocated inside the plant. Immunox is a penetrant that is xylem mobile, therefor, not totally systemic or amphimobile.

Xylem-mobile fungicides (also called acropetal penetrants ) move upward from the point of entry through the plant’s xylem.

Amphimobile fungicides (also called true systemic penetrants) move throughout the plant through its xylemand phloem.

Locally systemic fungicides have limited translocation from the application site

Translaminar fungicides are absorbed by leaves and can move through the leaf to the opposite surface they contact,but are not truly systemic and do not move throughout the plant.

In summary, systemic fungicides work

by becoming absorbed into the plant tissues and protecting the plant

from fungal diseases as well as ridding the plant of any existing

diseases. Some systemic fungicides are locally systemic, meaning that

the chemicals aren't transmitted very far from the application site on

the plant. Other systemic fungicides are applied to and absorbed up

through the roots, moving throughout the rest of the plant. Eradicant fungicides can have systemic action, depending on which chemistry is chosen. Some are translocated within

the host tissue and are able to kill the scab fungus up to a certain

length of time after infection occurs. This is called the kickback or reachback

period. Because kickback periods may change, always check the label for

the most recent information. Kickback is calculated from the beginning of an infection period, as determined by the Mills and La Plante table.